Here’s a hypothesis for my economics-minded friends. The fundamental driver of economics is supply and demand. The more demand exceeds supply, the more profit a seller can demand from a buyer. And conversely, the lower demand is relative to supply, the less profit they can demand.

For instance, if I am selling a house in a hot Nashville market, I don’t have to take just *any* price. As a rational actor interested in maximizing my profit (hi Prof. Froeb!), I can bide my time and wait for a high bidder to come along. Conversely, if I’m selling in Flint MI, I would be wise to take the first semi-decent bid that comes along.

Let’s apply supply and demand to money itself. People want to borrow money (they are the “buyers”) and people who want to save money (they are the “sellers”). When the economy is booming, there are relatively more people borrowing than saving, so profits (ie, interest rates) go up. Conversely, if you’re in a Great Recession, more people are less interested in borrowing money, and profits (the interest rates) plunge.

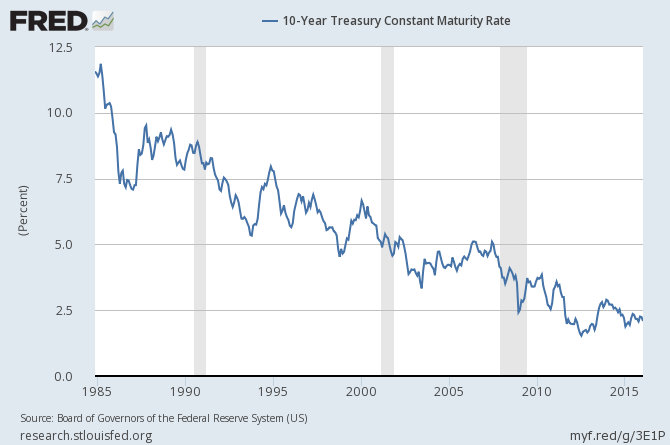

Now, let’s look at the interest rate the US Government pays on 10 year treasuries, ie. the profit that lenders can charge our government to borrow their money:

Notice that, while it does fluctuate around a bit, over the past 30 years it has trended downward, no matter how the economy is doing or what political party is in office at that time. That implies that the cause of lower interest rates is something else. And it’s a relatively smooth, constant decent. Something long-term, not day-to-day, is causing that trend.

My idea (and I’m happy to consider alternatives if anyone has a better idea) is simply that there is more money, than there is places to stick that money. Supply and demand tells you that prices (interest rates) will go down, which is exactly what we see.

Over the past 30 years the world has gotten wealthier, so there’s more money sloshing around that people are trying to save, but the growth in investment opportunities hasn’t kept pace with the growth in capital, so lenders are being forced to accept smaller and smaller profits.

If true, it would seem to have a number of “interesting” consequences on people’s long-term investment strategies (I am sure there are many, many more which have not occurred to me, so share if something comes to you!):

- People complain about government having too much debt. The bond market, on the other hand, is saying (via continually decreasing interest rates) that the government doesn’t have nearly *enough* debt.Based on that signal, a future government will likely increase borrowing. As you eventually have to pay the butcher, and poor/middle class people don’t have a lot of money, this implies substantially higher taxes on the wealthy at some point.

- Interest rates can’t go below zero (ignoring the “carrying costs” of holding cash), as people would just stick cash under their proverbial mattress and earn 0% rather than loan it out at a loss. If the trend on the graph continues, the 10 year Treasury rate will be 0% around July, 2021.What happens to the economy when we are in a world where there is more money trying to be saved, than there is investments for it to be saved in? Do rich people stop saving as much and start spending a proportionally higher amount of their income (which would help stimulate the economy), or do they have a “run on mattresses” (which would not).

Would the Federal government start limiting the amount the uber-wealthy can invest to preserve sufficient investment opportunities for the poor and middle class to allow them to retire?

- The 10-12% return the stock market “always” delivered in the past, may be lower for the foreseeable future. Which means people will need to save more money than before to retire with the same lifestyle, and this will reduce consumption in the present. This will hit equity prices eventually (which are already trading at well above their historic norms).

The “savings glut” problem is further compounded by income inequality, but I don’t have any good ideas what that means yet. I’ll show you my Nobel Prize in Economics when I understand them both…

As I have both a 401K and a desire to retire before I’m 90, I would be *delighted* to be wrong, but haven’t seen any data that would dissuade me from my thesis. I’m not sure what the future holds (or else I’d be typing this from my secret volcano lair instead of my cubicle at work), but anyone who expects the next 30 years of economics/politics/investing to look like the previous 30 years is probably crazy.